Dry shade is one of the most frustrating and challenging obstacles you’re likely to face as a gardener (it’s not much fun for the plants, either). Plants have all kinds of interesting adaptations to both shade and drought, but they’re almost always mutually exclusive: drought-resistant plants almost always need full sun to grow deep roots or thickened leaves, and plants that tolerate shade have increased photosynthesis, which means they lose more water.

It’s true that plants adapted to dry soil and shade aren’t as common as plants adapted to one or the other, but there are still plenty of them. They’re just not discussed as much in gardening circles because of their unique habitat preferences — although some, like coral bells and cyclamen, have achieved widespread popularity, either because of their ease of growth or their striking appearance (and often both).

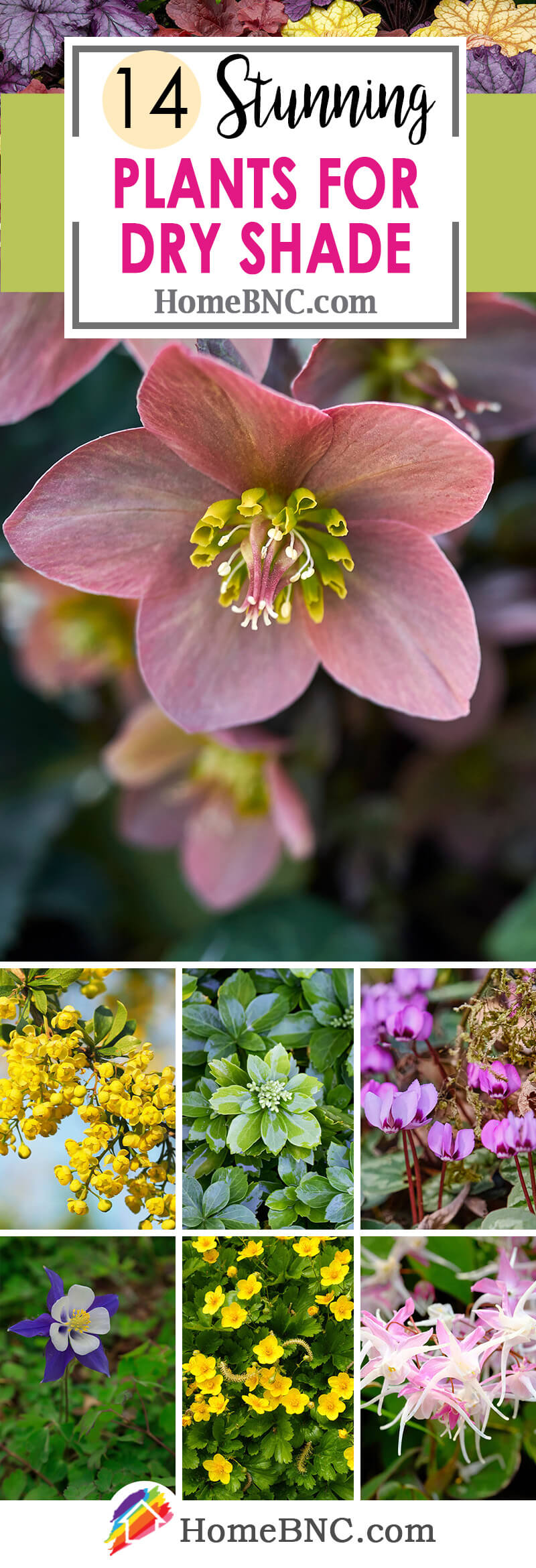

Below, you’ll find 14 of the very best ornamentals for dry shade. From low, creeping ground covers to sturdy shrubs, these species don’t compromise between environmental hardiness and aesthetic appeal. In fact, if your garden isn’t dry and shady, you might find yourself wishing that it were by the end!

First, you’ll find a primer on dry shade: why it’s such a challenge for ornamental plants, as well as a few tips for optimizing dry shade areas in your garden. Even if you don’t fall in love with a single plant in this article (unlikely!), by the time you reach the end you will hopefully have learned enough to pick your own plants with confidence.

Key Takeaways

- Dry shade is a unique challenge for plants because most of their adaptations to one make them less suitable for the other. For example, many plants adapt to shade by growing bigger leaves (which is why so many shade ornamentals have massive foliage), which helps them catch more sunlight for photosynthesis. Unfortunately, it also increases evaporation, so they end up needing more water than a similar-sized plant with smaller leaves.

- This isn’t usually a problem, because shady habitats in nature are usually well-watered, and dry habitats are sunny. It stands to reason when you think about it: in nature, “shade” almost always means “trees,” and trees need a lot of water — so places that can support trees usually have a lot of water, and places that don’t have a lot of water generally don’t have a lot of trees.

- The exceptions to this rule are generally found in the middle: places that are wet enough to support trees (often trees that don’t need a lot of water), but where there isn’t much left over. The problem (for herbaceous plants) is compounded when the trees are particularly good at finding and exploiting water in the soil. If you’ve ever been in a pine forest, you’ve probably noticed that the ground is usually free of shrubs and herbaceous plants. This is because pine trees have robust root systems that allow them to take up so much water that there isn’t any available for smaller plants.

- Pines aren’t the only trees that compete with herbaceous plants for water – or even the best known. If you’ve ever tried gardening under oaks, you’ve probably experienced the frustration of watching your perennials wilt from a lack of light, water, or both. Like pines, oaks have extensive root systems, both horizontally and vertically – and because their roots are close to the soil surface, they can starve smaller plants of water even when there is enough for everyone.

- Plants adapt to dry shade in different ways, depending on the specific environmental conditions: temperature, humidity, soil depth, shade intensity, and whether drought and canopy cover are seasonal or continuous. All of these are important things to know about your dry shade too, because they’ll influence which plants can grow there. For example, oaks and pines both have dry, shaded conditions under their canopy — but the soil around pines can be deep enough to plant fairly large species, while the shallow roots of oaks may not allow you to plant anything in the ground. In this case, a raised bed can sometimes be a great solution.

- Another important factor is how much supplemental water you can give your plants. If you can irrigate your plants, you have a lot more options than if they have to rely on natural precipitation. Read carefully about any plants that are advertised as good for dry shade: often, this just means that they like well-drained soil, and they may actually be quite thirsty!

14 Ideal Garden Plants for Dry Shade

1. Epimedium, Barrenwort, Fairy Wings (Epimedium spp.)

When it comes to dry shade-adapted ornamentals, there’s epimedium, and there’s everything else. Precious few plants tolerate deep shade and drought better than these hardy, evergreen perennials, which can hold their own against neighboring trees many times their size. Their heart-shaped, evergreen foliage is dense enough to make an effective ground cover, and some varieties boast a reddish wash that is an attractive complement to their sinuous curves.

However, what really sets epimediums apart from other dry shade plants is their flowers: they’re prolific, brightly colored, and in most species, very strange-looking: the four inner petals are nested in four extravagantly long, thin sepals, and they look like they might jump down from the plant at any moment and make a run for it. However, epimediums are not the kind to cut and run. Think of them as floral duct tape for dry shade: if it can’t be fixed with epimediums, it can’t be fixed.

There’s quite a bit of variability among species and cultivars, both in appearance and hardiness, and a little prior research will go a long way in picking the perfect specimen. In general, European and Mediterranean plants are hardier and more drought-resistant, while the plants originating in Asia – like E. grandifolium, the progenitor of some of the most popular hybrids – are showier. Then again, these plants are tough enough – and attractive enough – that most gardeners won’t have to choose.

2. Coral Bells (Heuchera spp.)

Coral bells nearly earn their spot on this list on the strength of their namesake flowers alone, which have a dainty, whimsical appearance similar to bleeding-hearts. However, in most varieties, the real star (or co-star) of the show is the foliage: big, lush, toothy, and available in seemingly every conceivable shade and hue, as well as a few that are frankly inconceivable. It’s hard to believe, looking at these surreal mounds of neon leaves, that they’re native to North America (and to the desert Southwest, at that), but make no mistake: these plants have plenty of native grit. Once established, they’re virtually maintenance-free, and resist drought, disease, and deer with equal aplomb, and with a hardiness spanning zones 3 to 9, there’s scarcely a garden in the country where they won’t grow.

3. Hostas (Hosta)

Hostas and coral bells go so well together, they ought to have their own sitcom. Both species are shade garden royalty, and pair big foliage with dainty, bell-like flowers. Though they may lack the eye-popping colors of coral bells, hostas are just as diverse when it comes to patterns and shades of green, and their cool, smooth lines are the perfect yin to coral bells’ extroverted yang.

Because of their lush appearance, many people assume hostas are thirsty plants, but they’re actually relatively drought-tolerant once their roots are established, and in areas with cooler summers they can thrive in dry shade with very little maintenance. One word of caution about hostas, however, is that they can be magnets for pests, from slugs to deer – so be prepared to defend your plants.

4. Lady’s Mantle (Alchemilla mollis)

Lady’s mantle is a perennial with deep (historic) roots, as you might guess from the antiquated common name. In Europe, and especially in the British Isles, it’s an iconic garden plant, both because of its softly structural silhouette and its ease of growth. (Also, perhaps, because it looks its best immediately after a rainstorm: fine hairs on the leaves catch raindrops, which produces an alluring glitter.)

Lady’s mantle is an easygoing plant, and isn’t picky about soil as long as it’s not waterlogged. While it’s not a true full-shade plant, it can often be the perfect pick for dry, shady patches, especially in the southern end of its hardiness range (zones 3 to 7). It makes an excellent underplanting, or as part of a mixed border – but resists the urge to over-plant, as lady’s mantle self-seeds easily and prolifically.

5. Oregon Grape (Berberis aquifolia)

Don’t let the name fool you: Oregon grape is about as closely related to grapes as you are to Genghis Khan. It isn’t even a vine, but a prickly, evergreen shrub, with glossy leaves remarkably similar in appearance to English holly — but it’s not related to holly, either. One of its closest relatives, in fact, is none other than epimedium, which ought to give you a hint as to its dry-shade pedigree. The small, early-blooming yellow flowers of Oregon grape don’t look much like the alien shapes of epimedium, but they’re a perfect fit for the coppery foliage, and seem to glow from within even in deepest shade.

Oregon grape’s native habitat is Douglas fir forest from Alaska to California, and like many plants from the upper Pacific Coast, it has fairly limited hardiness, being accustomed to the moderating influence of the ocean. It’s hardy between zones 5 and 8, but in northern gardens it will be happiest in a protected location, as it is easily damaged by freezing winds. One more thing: if you want any “grapes,” you’ll have to plant two or more of them.

6. Barren Strawberry (Waldsteinia ternata)

Barren strawberry gets its name from its fruits, which look like strawberries but are inedible. However, its name is apt in more ways than one, because it’s also the kind of plant that can thrive in “barren” areas, and is a popular (flowering) groundcover in Southern gardens because of its heat tolerance. It’s hardy between zones 4 and 8, and easily adapts to a wide range of soils, including “problem” soils like chalk and clay.

Like its more famous namesake, barren strawberry spreads by “runners”, which is often a sign of latent aggression in a garden plant. Fortunately, because it grows in shade, barren strawberry tends to be slower-growing and less prone to weediness than other similar species. For gardeners who prefer ornamentals “Made in the USA,” there’s also a native species: W. fragarioides, the Appalachian barren strawberry.

7. Cyclamen (Cyclamen)

Cyclamens might not be the biggest or most versatile plants on this list, but what they lack in size, they make up for in sheer delightful oddity – and it doesn’t hurt that they tolerate drought and shade with ease. In fact, they might just be the quintessential dry shade ornamental: slow-growing, long-lived (up to 100 years or more!), and perfectly adapted to their unique niche.

Cyclamens have cleverly managed to avoid the problems of growing in shade by reversing the usual plant life cycle: dormant throughout the summer, they emerge in fall and send up their small but striking flowers in winter, which look uncannily like the bees that pollinate them. This willingness to take the “graveyard shift” comes at a price, namely a dislike of the cold, dry winters that most of the country is used to. In milder climates, though – for the hardiest varieties, zones 5 to 9 – these unique plants make a striking addition to the winter garden.

8. Columbine (Aquilegia spp.)

Although they’re only distantly related, columbines bear more than a passing resemblance to cyclamens, both in their overall form and their preferred growing conditions. Both are early-blooming summer-dormant perennials with large, flat leaves and eye-catching flowers, precariously balanced on threadlike stems. Unlike cyclamens, columbines are quite flexible geographically, flourishing from zones 3 to 8 – almost anywhere between Mexico and Canada!

Columbines have been well-loved and much planted on both sides of the Atlantic, and are native to both Europe and the Americas. Between natives, exotics, and hybrids, you can find them in a rainbow of different colors, sometimes on the same flower! One thing to keep in mind about columbines is that like cyclamens, they usually go dormant in the summer. It’s a good idea to mix columbines with later-flowering perennials, which are coming up just as the columbines are going dormant.

9. Hellebore, Lenten Rose (Helleborus orientalis)

Lenten rose is an odd plant in many ways: it’s a very early-blooming perennial, often flowering in late February just as the eponymous holiday is getting underway. Its flowers are also amazingly long-lived – or at least look that way: their large, colorful “petals” are actually the sepals that surround the actual flower. Since they’re not part of the reproductive equipment, they remain on the plant long after the flowers drop off.

The foliage is just as unique – and just as long-lasting – as the flowers, looking more like palm fronds than leaves. These are evergreen in much of the country, and while they may die back in more northern climates, the roots have an impressive frost hardiness (zone 4). Plant them in the back of your perennial beds for an evergreen backdrop that will take center stage just as the frost is melting!

10. Solomon’s Seal (Polygonatum spp.)

Solomon’s seal doesn’t call a lot of attention to itself with its large size or bright colors. It has a subtle appeal that asks you to slow down and look closer. Large chartreuse leaves zigzag up its arching, unbranched stems, and in the spring these are adorned with delicate off-white flowers that hang singly or in pairs from the underside of the stem, a bit like hostas or coral bells.

The combination of simple structure and intricate detail makes Solomon’s seal a great partner for other “minimalist” ornamentals: bleeding hearts, ferns, and lungworts. It’s equally lovely when planted en masse, and it will slowly expand to form large, airy colonies reminiscent of autumn or ostrich fern. The most common ornamental species, P. biflorum, is native to eastern Asia, but the native P. pubescens or hairy Solomon’s seal is nearly identical, apart from being shorter overall.

11. Western Sword Fern (Polystichum munitum)

Many people think of ferns as lush, tropical plants that you might find in a rainforest — the very opposite of a drought-tolerant plant. Yet many ferns are highly drought-resistant, and an amazing number of species are found in desert environments! Some of the most popular ornamental ferns — ostrich fern, Christmas fern, bracken, etc. — make great dry-shade plantings, and one of the best of these is the Western sword fern.

Western sword fern is a close relative of the Christmas fern. It’s native to the Western United States, where it grows abundantly in dry pine forests and rocky wooded slopes, so dry shade is nothing new for it. It’s also an exceptionally pretty fern, forming big but tight clumps of dozens of fronds that (unlike many similar ferns) are evergreen between zones 5 and 9. In spring, the young fronds emerge as whimsical fiddleheads that “bloom” along with the rest of your perennials.

12. Sedges (Carex spp.)

Sedges are seriously underused in shade gardens, particularly in areas with hotter summers like the Deep South. While they’re not closely related to grasses, they’re almost indistinguishable for much of the year, and often fill similar ecological niches in forested ecosystems that grasses do in open ones. It’s hard to say anything more specific about sedges, even just the “true” sedges in the Carex genus, because they’re so extraordinarily diverse: over 2,000 species are found worldwide, ranging from petite clumps to shaggy manes well over a foot in height.

Sedges are widely available in most garden stores, but they’re usually not identified very precisely; for dry shade, your best bet is to go with a native species. Pennsylvania sedge (C. pensylvanica) is one of the most drought-tolerant of these, and boasts impressive frost hardiness (3 to 8) as well as a spreading growth form that makes it a viable lawn alternative.

13. Japanese Pachysandra (Pachysandra terminalis)

Japanese pachysandra is a tough-as-nails, evergreen ground cover that will happily occupy bone-dry shade where no other plants can survive. A relative of spurges (Euphorbia), its biggest dimension is horizontal rather than vertical: a few plants can quickly fill an edge or border while never rising above sock height. Pachysandra, like many spurges (with some notable exceptions), is also pest-resistant, due to toxic chemicals in the leaves, making this a real “plant it and forget it” perennial.

Almost. As with most “too tough to be true” plants, there are downsides to Japanese pachysandra, even if they aren’t immediately apparent. The first is that they’re susceptible to fungal pathogens like downy mildew, and may need to be thinned to improve air circulation. More importantly, in ideal growing conditions it can become weedy and even invasive. Before planting pachysandra, make sure it isn’t listed as invasive in your area – and be prepared to monitor your plants to ensure they don’t get out of hand.

14. Siberian Bugloss (Brunnera macrophylla)

Siberian bugloss has the look of a plant that belongs in the dappled light of the forest floor: it’s a low-and-slow, clump-forming perennial with big, heart-shaped leaves, which contrast with its impossibly delicate blue flowers, which bear a striking resemblance to forget-me-nots. Unlike its annual cousin, however, Siberian bugloss is quite well-behaved in a rock or shade garden. If given room and plenty of time, it can eventually form a continuous ground cover by means of underground rhizomes – but more often it will maintain a neat mound shape, making it the perfect companion for coral bells and hostas.

Though there aren’t yet many varieties of Siberian bugloss, the ‘Jack Frost’ cultivar is notable, and not just because it was awarded “Perennial of the Year” in 2012. Its silvery, variegated leaves make an intriguing contrast to the blooms, and it tolerates drought better than any other widely available cultivar.

14 Wonderful Drought-Tolerant Plants That Also Love Shade

If there’s one thing you should take away from this list, it’s that dry shade doesn’t have to be an obstacle to having a fabulous garden. These 14 species are some of the toughest, most beautiful, and widely used species — but there are many, many more! One thing to remember about dry shade is that it occurs in many different environments around the world, and manifests differently in each.

This means that the plants that will grow in your dry shade garden may not be the same as the ones that do well somewhere else. Don’t get discouraged if a plant that’s advertised as “good for dry shade” doesn’t work in your yard — you can learn just as much from the plants that don’t grow in your garden as you can from the plants that do.

Don’t be afraid to experiment and to try different plants until you find the ones that work for you, and remember: any problem your garden may have is a problem that’s been confronted and solved by plants somewhere in the world. The secret to growing an amazing garden isn’t buying the right fertilizer or the right soil — it’s knowing the right plants! If you do, you can rely on them to take care of themselves, whatever the world might throw at them.

Frequently Asked Questions About Plants for Dry Shade

What plants grow best in dry conditions?

This is a tricky question to answer because every plant grows differently, but it would be hard to argue with the answer most people would give: cacti. Nearly everything about these plants is optimized for water efficiency, from their succulent stems to their protective spines (which are actually modified leaves). Then again, “best” is always relative when it comes to plant adaptations, because every adaptation involves a trade off: cacti are best adapted to hot deserts, but their succulent stems can be injured by freezing, and they are relatively rare in cold deserts like those found in Central Asia or Patagonia.

What does dry shade mean?

Dry shade means different things in different regions, and plants adapt to it differently depending on what causes it. In most cases, it’s a result of unequal competition between trees and herbaceous plants: trees, with their large and extensive root systems, are more efficient at harvesting water than more shallowly-rooted plants. This competition is especially intense when the shade trees are themselves shallowly-rooted, like oaks: their roots compete directly with smaller plants growing beneath them, and because of their size, they usually win.

Dry shade can also be found in ecosystems with intense seasonal water limitation. The pine forests that grow along the Mediterranean are moist enough to support understory plants in the winter, but not in the summer. Plants in this region have developed some ingenious strategies for exploiting this seasonality: cyclamens, for example, simply go dormant in the summer to avoid competing for water, and grow and bloom in the fall and winter.

What is the best Polystichum for dry shade?

In North America, the native holly fern or sword fern (Polystichum munitum) grows abundantly in dry forests across the western US. It is one of the hardiest and most drought-resistant ornamental species, and is particularly well-suited for dry shade.

What is the most drought-tolerant Epimedium?

As noted above, garden epimediums are mostly from Europe (and a few from Japan), though a number of Chinese species have recently become more widely available. The European species are usually considered the most drought-tolerant, as are many hybrids of Asian and European species. The newer Chinese epimediums aren’t necessarily less drought-tolerant, but they’re a bit of an unknown quantity, as many have not been studied as thoroughly as the older European and Japanese varieties.

What is the most drought-tolerant plant in the world?

Believe it or not, it’s a species of moss called Selaginella lepidophylla. Unlike most plants that we think of as “drought-tolerant,” it doesn’t have any special adaptations to prevent water loss – but it has the amazing ability to survive for years, dormant, in a state of almost total desiccation, only to revive and resume growth in the next rain. In fact, most of the world’s really drought-tolerant plants are simple organisms like mosses and ferns, which are less affected by water loss than plants with vascular tissue.